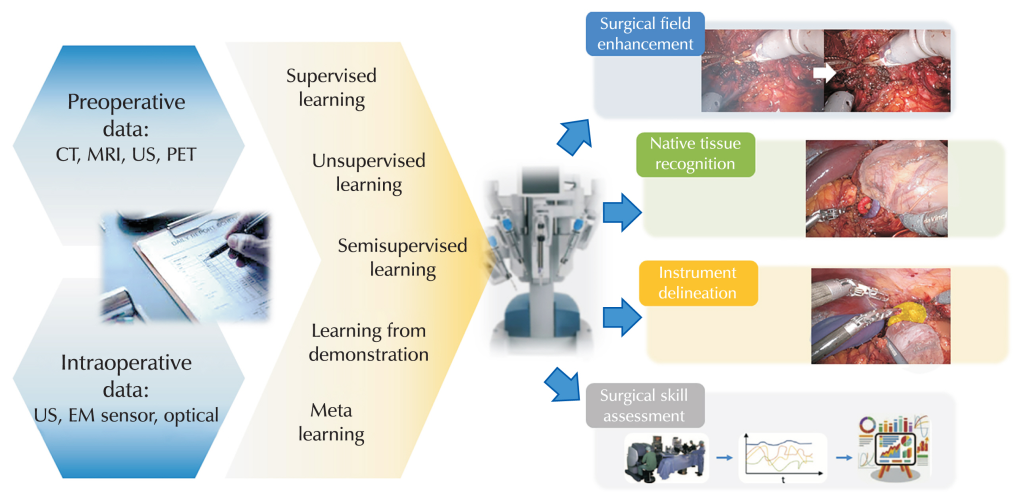

Physical AI in robotic surgery and factories combines advanced machine learning with machines that can sense, move and adapt in the real world. In both domains, the key shift is from pre‑programmed motion to systems that perceive their environment, make context‑aware decisions and collaborate with humans.

In robotic surgery, one prominent example is the integration of vision–language models with the widely used da Vinci system, allowing its tiny robotic arms to autonomously perform subtasks such as tissue lifting, needle handling and suturing after being trained on hours of surgical video. During experiments, the system even recovered a dropped needle without explicit programming, demonstrating adaptive behaviour characteristic of embodied intelligence in the operating room.

Another surgical example is the Smart Tissue Autonomous Robot (STAR), which has autonomously performed soft‑tissue procedures in animal models using computer vision and machine learning to adapt to tissue movement and deformation in real time. AI‑guided suturing systems that plan stitch placement and control robotic tools for bowel anastomosis or spinal screw insertion have shown reduced errors, less blood loss and shorter procedure times compared with purely manual techniques.

Physical AI also appears in “collaborative” surgical platforms such as Moon Surgical’s bedside robot, which adds extra robotic arms that can automatically position cameras, hold instruments and maintain tissue exposure while the surgeon operates. Here, AI tracks the surgeon’s tools and the surgical field so the robot anticipates where to move, reducing the surgeon’s physical strain and cognitive load without removing human control over key decisions.

In factories, physical AI powers collaborative robots (cobots) that work safely alongside people, dynamically adjusting speed, force and trajectory based on sensor input rather than rigid cages and fixed routines. Automotive manufacturers such as General Motors use AI‑enabled cobots for tasks like adhesive application and precision assembly, where the robots learn from human workers’ motions and continuously refine their paths to improve ergonomics, quality and throughput.

More broadly, AI‑driven industrial robots in “robotic factories” handle complex assembly, welding, painting and quality inspection while linking to digital twins of production lines for real‑time optimisation. Systems such as exoskeletons for assembly‑line staff, which predict user movements and deliver just‑in‑time support, illustrate a hybrid model in which physical AI augments rather than replaces human labour on the shop floor.

Physical AI in robotic surgery faces a mix of technical, clinical, organisational and ethical limitations that still constrain how far and how fast it can be adopted. These limitations are not just bugs to be fixed; many reflect fundamental tensions between safety, autonomy, cost and trust in high‑stakes clinical environments.

First, data and algorithm limits remain a major bottleneck. High‑quality, diverse, well‑annotated surgical datasets are still scarce, so models may not generalise across hospitals, patient populations or rare complications. Soft‑tissue surgery is especially difficult: anatomy deforms, bleeds and moves with breathing and heartbeat, which makes it hard for vision and control algorithms trained on cleaner data to stay robust in messy real operations. Simulation environments often simplify physics and tissue behaviour, so policies learned “in silico” can fail when transferred to real patients.

Second, current systems struggle with perception and real‑time reliability in complex scenes. Cameras can be obscured by blood, smoke, fogging or instruments, and lighting can change quickly as the endoscope moves or cautery is used. Accurately distinguishing healthy from diseased tissue and tracking tools in these conditions is still error‑prone, which limits how much autonomy surgeons are willing to delegate. Small kinematic inaccuracies in commercial platforms, such as joint measurement errors and mechanical slack, also introduce noise into the data on which learning algorithms depend.

Third, there are unresolved clinical and operational questions. Many reviews note that, for several procedures, AI‑robotic surgery has not yet shown clear, consistent superiority over conventional laparoscopy in terms of operative time, complications or cost‑effectiveness. Systems are expensive to purchase and maintain, require costly disposable instruments, and add setup time and workflow complexity, which is particularly challenging in resource‑constrained hospitals. Limited long‑term outcome data and the need for continuous validation mean that clinicians remain cautious about scaling these tools beyond early adopters and specialised centres.

Fourth, technical integration and infrastructure pose practical limits. AI modules must interoperate with existing robotic platforms, imaging systems and hospital IT, but interfaces, standards and cybersecurity practices are still fragmented. Latency, network reliability and data‑governance constraints can all affect whether real‑time decision support is actually usable in the theatre. In orthopaedic and other procedures, teams often need to keep full conventional instrument sets available as backup, which reduces the efficiency gains expected from robotics.

Fifth, ethical, legal and human‑factor issues remain unresolved. Many models function as “black boxes”, making it hard for surgeons to understand or contest their recommendations and for regulators to assess safety. Questions about accountability in the event of an AI‑related error, algorithmic bias, informed consent and data privacy do not yet have clear, widely accepted answers. There is also concern that over‑reliance on automation could deskill surgeons over time, potentially increasing risk if systems fail or need to be overridden in emergencies.

Finally, there are inherent limits to full autonomy in such a safety‑critical domain. Regulatory frameworks for highly autonomous surgical robots are still evolving and are deliberately conservative because errors can be catastrophic. As a result, most deployed systems remain at low levels of autonomy, assistive rather than fully independent,with a human surgeon firmly “in the loop”. For the foreseeable future, these constraints mean physical AI in surgery is more likely to augment human skill than replace it, and progress will depend as much on governance, training and evidence generation as on advances in algorithms or hardware.

Leave a Reply